When someone mentions the phrase Exclusion Zone, the first thing that comes to mind is Chernobyl. But in addition to the famous Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, there are numerous such restricted areas that exist in the world today. They also have radiation exposure to abnormally high levels and their own interesting story.

What does Exclusion Zone mean?

Exclusion Zones are commonly used in the construction industry worldwide. For this purpose they are defined locations to prohibit the entry of personnel into danger areas, established through the risk assessment process for a construction activity. Typically, Exclusion Zones are set up and maintained around the plant and below work at height. Similarly, Exclusion Zones have been established due to natural disasters.

According to Collins Dictionary:

An exclusion zone is an area where people are not allowed to go or where they are not allowed to do a particular thing, for example because it would be dangerous.

But in our case we are interested in Nuclear Exclusion Zones and based on this information we can define it as: The areas around the site’s nuclear disasters, which have been closed off, because of the ongoing dangers of radiation and its effects.

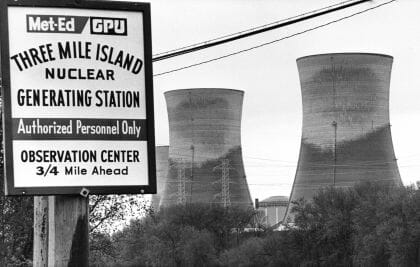

The Three Mile Island, US

The Three Mile Island power station is near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in the USA. On 28th March 1979, radioactivity was released into the atmosphere and contaminated coolant escaped into the nearby river. It is the most significant accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant history. The Three Mile Island accident caused concerns about the possibility of radiation-induced health effects, principally cancer, in the area surrounding the plant.

The studies found that the radiation released during the accident were minimal, well below any levels that have been associated with health effects from radiation exposure. The average radiation dose to people living within 10 miles of the plant was 0.08 millisieverts (mSv), with no more than 1 mSv to any single individual. The level of 0.08 mSv is about equal to a chest X-ray, and 1 mSv is about one-third of the average background level of radiation received by US citizens in a year.

In order for the lifetime risk of developing cancer to increase even slightly, doses above 100 mSv during a very short time frame would be required. A dose of 100 mSv would increase the lifetime cancer risk by approximately 0.4%, to be compared with the 38-40% of all US citizens who would develop cancer at some point during their life from all other causes.

The site and reactor were mostly contaminated. It has taken 14 years and cost $1 billion to clean up the area. Up to date, the ruins are still radioactive.

White Sands, New Mexico, US

More than 70 years ago the first ever nuclear bomb was detonated at the White Sands missile testing ground. The 18-kiloton bomb was detonated in 1945, causing a 12-km high mushroom and heard 320 km away. The sand at the site turned into a green radioactive gas called Trinity.

The first atomic bomb test 60 miles from White Sands NM

Source: Courtesy Los Alamos Photographic Laboratory

The soil at the center of the Trinity Site is still slightly more radioactive than the surrounding soil—about 10 times greater than the region’s natural background radiation. Still, that extra radioactivity results in a very small dose: if you were to stand at the center of the site for an hour, you would get a dose of about 0.01 mSv.

Asse storage facility, Germany

The Asse mine is a former salt mine used as a deep geological repository for radioactive waste in the Asse Mountains of Wolfenbüttel, Lower Saxony, Germany. It was developed between 1906 and 1908 to a depth of 765 meters.

In 1965, the extraction of potash salt in the Asse stopped. After it was shut down, the nuclear waste was officially put there for “research purposes” until the end of the 1970s. But in reality, the mine was a repository.

The mine’s publicly owned operating company applied to officially close the facility in 2007. After media reports of radioactive saltwater leakages, the operator was accused of misinforming the supervising authorities, a claim that was later officially confirmed. In 2010 the Federal Office for Radiation Protection (BfS, Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz) began an inventory to take stock of the radioactive waste stored in the Asse mine, finding 14,800 containers with undeclared content. The number of containers with medium-level radioactive waste had to be revised upwards from 1,300 to 16,100 and the total quantity of plutonium from 6 to 28 kilograms.

Nuclear waste has been stored in the Asse storage facility for over 50 years, a salt mine meant to protect the radioactive waste for 100,000 years in Germany. 12,000 liters of water drip into the site daily, causing the drums to rust and resulting in the release of radioactivity. It is impossible to get close enough to begin a cleanup program.

There are almost no places on Earth that have not been explored much by people. By the early 21st century, it seems only the highest mountain peaks and the most remote corners of the ocean and deserts fall into the category of areas not frequently visited by human beings. However, there are more large human-free zones that were made so intentionally—because of serious nuclear accidents.

In the first part, we figured out what is the Nuclear Exclusion Zone, examined the most significant accident in the U.S, visited the place where the first ever nuclear bomb was detonated and explored one of the deepest geological repositories for radioactive waste in Germany.

Nevada Proving Grounds

The Nevada Test Site (NTS), 65 miles north of Las Vegas, was one of the most significant nuclear weapons test sites in the United States. Nuclear testing, both atmospheric and underground, occurred here between 1951 and 1992.

On January 27, 1951, nuclear testing at the NTS officially began with the detonation of Shot Able, a 1-kiloton bomb, as part of Operation Ranger. Between 1951 and 1992, the U.S. government conducted a total of 1,021 nuclear tests here. Out of these tests 100 were atmospheric, and 921 were underground. Test facilities for nuclear rocket and ramjet engines were also constructed and used from the late 1950s to the early 1970s.

A November 1951 nuclear test at Nevada Test Site, Operation Buster–Jangle “Dog”.

The atmospheric nuclear tests caused concern about potential health effects on the public, and environmental dangers, due to nuclear fallout. On August 5, 1963, President Kennedy, along with the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, signed the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. This prohibited nuclear weapons tests and nuclear explosions underwater, in outer space, and in the atmosphere.

There have been various debates over how much radiation exposure was caused by tests. Fallout from the tests drifted across most of the U.S. One major example of this is St. George, Utah. Particles that spread, such as iodine-131, can enter the body through contaminated food, drinks, or air, and eventually lead to cancer or birth defects.

Cancer rates in this area increased from 1950 to 1980, and many citizens of St. George now believe that the testing has caused deaths, cancer, and a variety of health issues in their families.

A study done in the 1990s determined that soldiers who witnessed testing at the NTS were more likely to either be diagnosed with cancer, or to die from cancer, later in life. In total, one hundred and nineteen atomic devices in the area North-west of Las Vegas and more than 1,000 nuclear tests were conducted underground. The area was finally decommissioned in 1992.

Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan

The Semipalatinsk Test Site, also known as “The Polygon”, was the primary testing venue for the Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons. It is located on the steppe in northeast Kazakhstan (then the Kazakh SSR), south of the valley of the Irtysh River.

An image from the first Soviet test of a thermonuclear device on 12 August 1953. It released about 25 times as much energy as the US bomb dropped at Hiroshima, Japan.

Credit: Lebedev Physics Inst. (FIAN)/Hulton Archive/Getty

The Soviet Union conducted 456 nuclear tests at Semipalatinsk from 1949 until 1989 with little regard for their effect on the local people or environment. The full impact of radiation exposure was hidden for many years by Soviet authorities and has only come to light since the test site closed in 1991.

Source: Nature

Soil, water, and air remain highly irradiated in the fallout area, where according to scientists the level of radiation is 10 times higher than normal.

The human suffering that took place at the site was well-documented, even before testing ended in 1989 and the site officially closed on August 29, 1991. Some 200,000 villagers essentially became human guinea pigs, as scientists explored the potential and dangers of nuclear weapons. Residents were reportedly ordered to step outside their homes during test blasts so that they could later be examined as part of studies on the effects of radiation. Some locals can describe — from first-hand experience — what a mushroom cloud looks like.

Source: Nature

One in every 20 children in the area is born with serious deformities. Many struggle with different types of cancer and more than half of the local population has died before reaching the age of 60.

“Almost all my classmates and friends have died,” says 50-year-old farmer Aiken Akimbekov, a native of the village of Sarzhal, located near the so-called “atomic lake” formed by a powerful nuclear explosion in the mid-’60s.

When the test site was closed, Kazakhstan was faced with the question of how to decontaminate the land and what to do with the military-industrial complex that remained on the territory of the test site.

Some parts of the area are still so contaminated that they have to be covered with huge, two-meter thick steel plates to contain the radiation.

Fukushima’s Nuclear Exclusion Zone

The Fukushima nuclear accident – a disaster which rivaled the magnitude of Chernobyl, began on March 11, 2011, after a massive offshore earthquake produced a tsunami that washed ashore and damaged the backup generators of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which located on the eastern shore of Japan’s Honshu Island.

The map shows the nuclear exclusion zones around Chernobyl and Fukushima.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc./Kenny Chmielewski

Regarding to the studies release of harmful radioactive pollutants or radionuclides, such as iodine‑131 (which has a half-life of 8 days), cesium‑134, cesium‑137 (which has a 30-year half-life), strontium‑90, and plutonium‑238 and many others.

A significant problem in tracking radioactive release was that 23 out of the 24 radiation monitoring stations on the plant site were disabled by the tsunami.There is some uncertainty about the amount and exact sources of radioactive releases to air.

Satellite image of damage at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan following the March 11, 2011, earthquake and tsunami.

Source: DigitalGlobe

Major releases of radionuclides, including long-lived caesium, occurred in air, mainly in mid-March. The population within a 20km radius had been evacuated three days earlier.

By the end of 2011, Tepco had checked the radiation exposure of 19,594 people who had worked on the site since 11 March. For many of these both external dose and internal doses (measured with whole-body counters) were considered. It reported that 167 workers had received doses over 100 mSv. Of these 135 had received 100 to 150 mSv, 23 workers 150-200 mSv, three more 200-250 mSv, and six had received over 250 mSv (309 to 678 mSv) apparently due to inhaling iodine-131 fume early on, but these levels are below those which would cause radiation sickness.

Japan’s regulator, the Nuclear & Industrial Safety Agency (NISA), estimated in June 2011 that 770 PBq (iodine-131 equivalent) of radioactivity had been released, but the Nuclear Safety Commission in August lowered this estimate to 570 PBq. The 770 PBq figure is about 15% of the Chernobyl release of 5200 PBq iodine-131 equivalent. Most of the release was by the end of March 2011.

Tests on radioactivity in rice have been made and caesium was found in a few of them. The highest levels were about one quarter of the allowable limit of 500 Bq/kg, so shipments to market are permitted.

According to the Stanford research, radiation from Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster may eventually cause approximately 130 deaths and 180 cases of cancer, mostly in Japan.

Did we miss something? Drop us a line and we’ll be sure to include it.

ChernobylX

ChernobylX

ChernobylX

ChernobylX